|

Modern African stone sculpture is not "traditional", although much of its subject matter has traditional roots. There were few, if any, individual sculptors working in stone in the first half of the 20th century but following the opening in 1957 of the Rhodes National Gallery in Salisbury, its first Director, Frank McEwen, encouraged local artists to explore that medium. Within a few years, a group of local artists including Thomas Mukarobgwa, Joram Mariga and his nephew John Takawira were learning the necessary skills, mainly carving insoapstone. This budding art movement was relatively slow to develop but was given massive impetus in 1966 by Tom Blomefield, a white South-African-born farmer of tobacco whose farm at Tengenenge near Guruve had extensive deposits of serpentine stone suitable for carving. A sculptor in stone himself, he wanted to diversify the use of his land and welcomed new sculptors onto it to form a community of working artists. This was in part because at that time there were international sanctions against Rhodesia’s white government led by Ian Smith, who had declared Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965, and tobacco was no longer able to generate sufficient income. Appropriately, Tengenenge means “The Beginning of the Beginning” – in this case of a significant new enterprise that has lasted through to the present day.

Further details of the establishment of the "first generation" of new Shona sculptors are given in the individual biographies of its leading members: Bernard Matemera, Sylvester Mubayi, Henry Mukarobgwa, Thomas Mukarobgwa, Henry Munyaradzi, Joram Mariga, Joseph Ndandarika, Bernard Takawira and his brother John. This group also includes the famed Mukomberanwa family (Nicholas Mukomberanwa and his protegees Anderson Mukomberanwa, Lawrence Mukomberanwa, Taguma Mukomberanwa, Netsai Mukomberanwa, Ennica Mukomberanwa, and Nesbert Mukomberanwa) whose works have been featured worldwide. Works by several of these first generation artists are included in the McEwen bequest to the British Museum.[1]

During its early years of growth, the nascent "Shona sculpture movement" was described as an art renaissance, an art phenomenon and a miracle. Critics and collectors could not understand how an art genre had developed with such vigour, spontaneity and originality in an area of Africa which had none of the great sculptural heritage of West Africa and had previously been described in terms of the visual arts as artistically barren.[2][3][4][5]

Fifteen years of sanctions against Rhodesia limited the international exposure of the sculpture. Nevertheless, owing mainly to the efforts of Frank McEwen, the work was shown in several international exhibitions, some of which are listed below. This period pre-independence witnessed the honing of technical skills, the deepening of expressive power, use of harder and different stones and the creation of many outstanding works. The "Shona sculpture movement" was well underway and had many patrons and advocates.

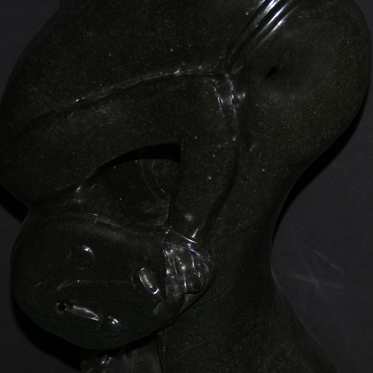

In spite of increasing worldwide demand for the sculptures, as yet little of what McEwen feared might just be an "airport art" style of commercialisation has occurred. The most dedicated of artists display a high degree of integrity, never copying and still working entirely by hand, with spontaneity and a confidence in their skills, unrestricted by externally imposed ideas of what their "art" should be. Now, over fifty years on from the first tentative steps towards a new sculptural tradition, many Zimbabwean artists make their living from full-time sculpting and the very best can stand comparison with contemporary sculptors anywhere else. The sculpture they produce speaks of fundamental human experiences - experiences such as grief, elation, humour, anxiety and spiritual search - and has always managed to communicate these in a profoundly simple and direct way that is both rare and extremely refreshing. The artist 'works' together with his stone and it is believed that 'nothing which exists naturally is inanimate'- it has a spirit and life of its own. One is always aware of the stone's contribution in the finished sculpture and it is indeed fortunate that in Zimbabwe a magnificent range of stones are available from which to choose: hard black springstone, richly coloured serpentine and soapstones, firm grey limestone and semi-precious Verdite and Lepidolite.

Jonathan Zilberg has pointed out that there is a parallel market within Zimbabwe for what he calls flow sculptures – whose subject-matter is the family (ukama in Shona) – and which are produced throughout the country, from suburban Harare to Guruve in the north-eastern and Mutare in the east. These readily available and cheap forms of sculpture are, he believes, of more interest to local black Zimbabweans than the semi-abstract figurative sculptures of the type mainly seen in museums and exported to overseas destinations. The flow sculptures are still capable of demonstrating innovation in art and most are individually carved, in styles that are characteristic of the individual artists.[14]

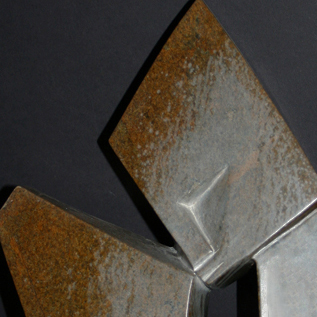

Some sculptors in Zimbabwe work in media other than stone. For example, at Zimbabwe Heritage 1988, Paul Machowani won an Award of Distinction for his metal piece "Ngozi" and in 1992 Joseph Chanota’s metal piece "Thinking of the Drought" won the same award. Bulawayo has been a centre for metal sculpture, with artists such as David Ndlovu and Adam Madebele. Arthur Azevedo, who works in Harare and creates welded metal sculptures, won the President’s Award of Honour at the First Mobil Zimbabwe Heritage Biennale in 1998.[15] Wood carving has a long history in Zimbabwe and some of its leading exponents are Zephania Tshuma and Morris Tendai.[3]

Source:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sculpture_of_Zimbabwe

- BACK TO TOP

|